The Monotype, or more accurately, the Monotype System, was brought to market in its most common current form in 1900. This followed a number of years of experimentation that created working machines that were displayed but not mass produced. While the competition between Linotype and Monotype was fierce, the printing industry realized there were strengths and weaknesses in both systems, and that the one chosen really depended on the needs of the individual printing plant, not the inherent superiority of one machine over the other.

The Monotype System

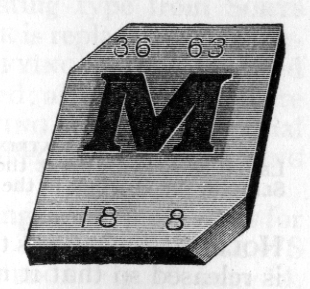

In many ways the key innovation in the Monotype System was not the mechanical device, ingenious as it was. To allow the casting of fully justified lines of type, Tolbert Lanston chose not to follow the path of Ottmar Merganthaler, who used tapered spacebands to create word spacing. He instead devised a unit system that assigned each character a value, from five to eighteen, that corresponded to its width. A lower case “i”, or a period would be five units, an uppercase “W” would be eighteen. This allowed the development of the calculating mechanism in the keyboard, which is central to the sophistication of Monotype set matter.

The original Monotype system consisted of a Composition Caster and separate keyboard, but over time, the Lanston Monotype Machine Corporation created a number of machines based on similar principles that expanded the range of type sizes that could be cast in-plant, as well as perfecting the free-standing Material Maker for leading, rule and fancy borders. (See the Leading and Border Casting Machines article for more information on the Material Maker.) These machines were all part of the grand goal of “non-distribution”, promoted by Monotype — forms that were entirely cast in-house could be dumped and re-melted, including leading and borders, rather than laboriously sorted for re-use.

The Monotype Composition Caster and Keyboard

While Tolbert Lanston came up with the basic concept of the Composition Caster (Comp Caster), it was John Sellers Bancroft who simplified and perfected the machine, allowing it to become a viable commercial product. A Comp Caster set-up requires a keyboard that resembles a typewriter on steroids — there are five QWERTY keyboards joined into one (upper and lower case Roman, upper and lower case italic, and small caps), with added keys for numbers, punctuation and ligatures. In general, the layout of the keyboard did not change when changing type style. This keyboard pneumatically punches a bond paper tape that resembles a player piano roll. This tape then controls the action of the casting machine. The keyboard mechanically tabulates the total width of the characters and word spaces in the line relative to the operator set line length. When the measure of the typed matter approaches the set line length, a bell sounds and the operator then punches in a code, which then informs the casting machine of the correct word spacing to be used on that line. The word spaces are then cast to that specific measure, rather than the traditional 3em, 4em, &c foundry spaces. The operator could also include letter spacing in the caster instruction tape.

This tape was then fed into the caster, tail end first, allowing the caster to read the line specific spacing requirements for that justified line. The remainder of the tape controls the X-Y movements of a frame (mat case) holding a 15×15 grid (later machines had a 15×17 grid) of 1/5 inch square matrices. This moves the correct character matrix over the mould for casting. The coordinates of the character in the case also informs the machine of the correct set-width of the character, which is adjusted prior to the casting stroke of the pump. The net result is fully justified individual pieces of type, ready to print. (Though leading would, in most cases, be added when the form was made up.)

Supporters of the Linotype and the Monotype engaged in endless debates regarding the superiority of one system over the other, but in practice the Monotype system did excel in several ways. Since the type is cast as traditional loose type, corrections and changes are much easier than with slug-cast material. The sophistication of the spacing capabilities of the Monotype made it the preferred device to set tabular matter such as railroad schedules. Finally, the character sets available to the Monotype user make it easier to do complex typesetting, such as math textbooks, or fine book work, though to be fair to the Linotype, enormous amounts of these latter types of work were done by skilled Linotype operators.

The Type and Rule Caster

With the correct paper tape, it is a simple matter to cast sorts, and even complete fonts of type, with the Comp Caster. That said there are issues with working in this way — unless a a printer was in the business of selling type as well as printing, tying up the machine in this way made little sense. The larger issue is that the Comp Caster has limits on font size — it is limited to a 6-14 point range. Monotype’s response to this was two-fold — they developed attachments for casting larger type and rule on with the Comp Caster, and they also developed a simplified version of the machine called the Type and Rule Caster.

The Type and Rule Caster, sometimes referred to as the Orphan Annie in the US (for no known reason), has much in common with the Comp Caster. It uses the same base, pump and pot, mould and mould set-width adjustment mechanism. Eliminated are tape reading system, the mat-case control system, and the mechanisms that change the set-width of the mould on each cast and move the type in lines. The machine casts sorts up to 36 point.

In a precursor to the Material Maker, Monotype also made a leading and rule casting attachment for both the Comp Caster and the Type and Rule Caster.

Other Monotype Machines

As Monotype Corporation built on the success of the original Composition Caster, they introduced other machines to compete for the printer’s dollar.

The Giant Caster was introduced in 1925—it is a sorts caster that complements the Comp Caster and the Type and Rule caster, capable of casting from 18 to 72 point type. It is also capable of casting leading.

The Super Caster was developed by the British arm of the Monotype Corporation in 1928 and eventually replaced the Giant Caster and the Material Maker in the Monotype product mix.

The Monotype Corporation purchased the Thompson Type Machine Company in 1929 and added that machine to its product line-up. It was produced until 1967. (See the Thompson Type Caster article for more information on that machine.) Modifications to the mould and mat holder converted the Thompson to use Lanston style display mats, but the majority of the machine remained unchanged from the original design.

Resources

- Hackleman, Charles W., Commercial Engraving and Printing. Indianapolis: Commercial Engraving Publishing Company, 1924.

- Hopkins, Richard L., Tolbert Lanston and the Monotype: The Origin of Digital Typesetting. Tampa: The University of Tampa Press, 2012.

- Huss, Richard E., The Development of Printers’ Mechanical Typesetting Methods 1822-1925. Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1973.

- Lanston Monotype Machine Company, The Monotype System: A Book for Owners and Operators of Monotypes. Philadelphia: Lanston Monotype Machine Company, 1916.

- Legros, Lucien Alphonse, and John Cameron Grant, Typographical Printing-Surfaces: The Technology and Mechanism of their Production. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1916.

- Wallis, Lawrence W., The Monotype Chronicles. monotypeimaging.com, ND.