Job printing—a nineteenth-century term—is traditionally defined as printing that uses display type and no more than a sheet or two of paper. Short as that definition is, it encompasses a world of paper items—tickets, letterheads, notices, invoices, vouchers, coupons, cards, labels, posters, receipts, and timetables, to name only a very few. A printer’s rhyming advertisement from the middle of the nineteenth century puts it this way:

Printing by hand,

Printing by steam.

Printing from type,

Or from blocks—by the ream.

Printing in black,

Printing in white

Printing in colors,

Of somber or bright.

Printing for merchants,

And land-agents too,

Printing for any

Who’ve printing to do.

Job printing is often neglected in studies of printing history, yet it is of vital importance to historians in other fields, and especially those who seek information about the daily life of ordinary citizens. Books may be biased and newspaper stories inaccurate, but ticket stubs and railway timetables seldom lie.

Job printing is as old as typography itself. (It might even be said to be older than typography, in the sense that wood-block images of saints and playing cards were forms of job printing.) Job printing often preceded book printing as the art of typography spread. The earliest piece of printing to bear a date set in type is the single-sheet Papal Indulgence of 1454, a year before the completion of Gutenberg’s 42-line Bible. An indulgence printed by Caxton in 1476 is the earliest surviving piece of English printing. The first printing in what is now the United States was The Oath of a Freeman, the broadside printed in Cambridge in late 1638 or early 1639. It was the subject of a sensational forgery several years ago, but no true copy is known to survive.

Early Job Printing

Some of the most interesting early examples of job printing were the lists of books for sale by the first printers. Among the best-known is Peter Schoeffer’s publisher’s list of 1469, which is both the earliest printed catalogue and the earliest type specimen. The text reads, in part, hec est littera psalterii, “this is the type of the Psalter.” Caxton’s similar notice of 1479, the first printed advertisement in the English language, was intended to be tacked to a door in some public place near his press in Westminster. He advertised that his “commemorations of Salisbury use” were “enpryntid after the forme of this present lettre,” and they were available “good chepe.” It ends with the plea, in Latin, not to tear down the notice.

The innovative master printer Erhard Ratdolt printed his trade-list in two colors in Venice in 1484. It was not until he returned to Augsburg in 1486 that he printed a full type specimen sheet, showing Roman, Greek, and Rotunda types. It survives in a single copy only.

Another of the best-known type specimen sheets is that of typefounder Conrad Berner, whose 1592 broadside shows types of Sabon, Garamond, and Granjon. This sheet was probably intended to be posted in booksellers’ stalls at the Frankfurt book fairs, according to Harry Carter. It, too, survived in a single copy until 1939 when it disappeared. As Carter notes, “it is a splendid array of typefaces.” Part of the effect is produced by the attractive piece border, the units of which are shown at the bottom of the specimen.

Later specimen sheets are more familiar. One such is Caslon’s famous 1734 broadside, later reprinted in Chamber’s Cyclopædia, and similar broadsides by Fry (1785) and Wilson (1783).

Rise of Job Printing in the 19th Century

Until the nineteenth century, job printing remained an adjunct of book and news printing shops. But the rise of trade following the Industrial Revolution called for a much larger volume of commercial printing. The job printer in the early part of the nineteenth century, operating a straining wooden press, had a tedious working day of ten to eleven hours, six days a week. The small forms were hard to print, and the slurring of ink on the wooden presses was hard to prevent. The development of iron jobbing presses, beginning in the late 1830s, brought automatic inking, better control, and much faster and cheaper work. George Gordon, inspired by a dream in which Benjamin Franklin appeared to him, perfected the familiar platen jobber. It became universal after 1858 and is still in use commercially in South America and Asia, and by amateurs in Europe and North America.

The opening of the Erie Canal in 1828 gave the developing interior of the country access to to the products of the seaboard and of Europe. That, and the later arrival of even cheaper rail transportation, meant a great increase in commerce and a rise in job printing. The following table of printers in New York City, taken from the American Dictionary of Printing and Bookmaking (New York, 1894) gives an indication of the dramatic rise:

| YEAR | NUMBER OF PRINTERS |

|---|---|

| 1800 | 75 |

| 1810 | 125 |

| 1820 | 200 |

| 1830 | 500 |

| 1840 | 1,200 |

| 1850 | 2,000 |

| 1860 | 3,000 |

| 1870 | 4.500 |

| 1880 | 6,000 |

| 1890 | 8,000 |

In the early part of the century, job printing existed only as a part of the work of every book and news printing establishment. But as commerce increased, job printing developed as a separate kind of business. Later in the century, and especially in the larger cities, there was enough work to allow even greater specialization, so that eventually there were shops doing only railway timetables, or posters, or handbills, and so forth.

Influences of Job Printing on Typographic Design

With increasing specialization, and as tastes changed, new type forms were developed. At the start of the century a few fonts of Caslon in various sizes sufficed, but by mid-century the ornate style we now call Victorian was flourishing, and printers had to stay abreast of fashion. The type founders’ specimen books of 1815 had shown the bare beginnings of “job letter;” by 1834 about 34 different styles were available, and by 1870 well over 1,000 separate type designs were on the market. The increase was made possible by technical advances in type founding, especially the invention of the automatic type casting machine of David Bruce Jr. in 1838 and the process of electrotyping of matrices for that machine a few years later.

Wood type also became available in a profusion of styles, with the invention of the mechanical router by Darius Wells of New York in 1827 making it possible.

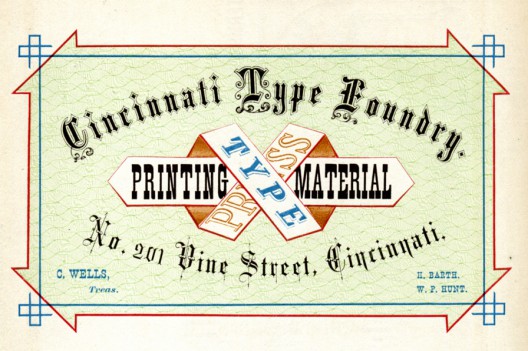

Lithography, which was introduced into the United States in Boston in 1828, increasingly competed with and influenced letterpress printing, especially in job work. By mid-century it was an important factor. The lithographic technique, in which designs were drawn by hand in pen or crayon on a lithographic stone, freed the printed image from the restricted, horizontal linear form of traditional typography. As this unconfined style became possible, and then fashionable, job printers who worked with metal types sought new ways to compete. With the help of type founders and makers of printing equipment, job printers devised ways to set type in diagonal and curved lines. They used wood-engraved and electrotyped illustrations, added curves and other decorative flourishes around their type. This effort at unrestrained arrangements using ornamentation and the great variety of type styles available, resulted in the characteristically ornate job printing associated with the middle of the century.

Foundations of Artistic Printing

One of the first American sample books for job printers was Oscar Harpel’s Typograph, or Book of Specimens, published in Cincinnati in 1870. It was a collection of job work he had produced for all kinds of businesses. The book was printed with great care and precision, and designed with imagination and sensitivity. Although ornate, the results are very attractive today. The book had a strong influence on job printing all over the United States for at least a decade after its appearance, and led to the “Artistic Printing“ style of the late century. Many of Harpel’s design tenets sound modern enough—grace, equilibrium, focus, harmony and contrast—but the results are unmistakeably nineteenth century.

Historical Job Printing Collections

The job printing shops of the nineteenth century turned out a steady stream of paper: stock certificates for western gold mines and midwestern beef packers; advertising cards for the mills of New England; bills of lading for clipper ships and steamships; and every other kind of printed scrap now found in attics and flea markets, as well as in the collections of great institutions. Some of the best known of these are the Bagford Collection at the British Museum, the Bella Landauer Collection at the New-York Historical Society, and those at the American Antiquarian Society, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the University of Michigan, Houghton Library at Harvard, and the New York Public Library.

Resources

- Carter, Harry. A View of Early Typography, Oxford, 1969.

- Hudson, Graham The Design and Printing of Ephemera in Britain and America, 1720-1920. Oak Knoll Press, 2008.

- Lewis, John. Printed Ephemera. Ipswich, 1962.

- Ringwalt.J. Luther American Encyclopaedia of Printing. Philadelphia, 1871 (“Job Printing,” pp. 257-9.)

- Steinberg, S.H. Five Hundred Years of Printing. London, 1959.